Lab life at Stanford during the COVID-19 pandemic

After a devastating and demanding several months, research at Stanford remains limited but could offer glimpses into how lab life might operate in the future.

When researchers at Stanford University prepared to shut down lab operations in mid-March last year amidst a worsening pandemic, every lab was faced with a unique set of challenges:

Biologist Jessica Feldman took stock of her C. elegans worms, prioritized the experiments that could be completed and froze the rest of the worms.

Physicist David Goldhaber-Gordon had to decide what to do with one of his group’s cryostats, a powerful but fussy instrument for performing experiments at near-absolute zero that requires in-person maintenance to keep it running safely.

Geological scientist Erik Sperling and his lab scrambled to complete experiments in progress.

And developmental psychologist Hyowon Gweon’s lab had halted all in-person experiments weeks before, but now faced the daunting task of converting to online-only studies for the first time.

“You can imagine the kind of panic that we were in when everything was shut down,” said Gweon, who is an associate professor of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “We suspected this would last for a while – although we didn’t expect it to last this long – so we restructured our lab to run studies online. It kind of felt like building a lab all over again.”

“We were working up until the bitter end,” said Sperling, assistant professor of geological sciences in the School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences. “Most people in the lab transitioned OK because they had papers to write and revise, but there are a couple people who were newer to the lab and they were more hurt by the shutdown.”

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

All of this happened during what the university called “Stage 0” of the research recovery process – the strictest operation condition. In Stage 0, only approved people could access campus labs and research spaces and only for approved, essential research functions, such as urgent COVID-19 research, certain medical research and necessary maintenance of lab equipment.

Stanford is presently at Stage 2 of research recovery, which allows for slightly more lab access. Some colleagues can see each other in person but they still move cautiously within imaginary 6-foot bubbles, must undergo regular testing for COVID-19 and wear personal protective equipment as they go about their tasks. And, as we experience another surge of infections, administrators are urging the community to continue working cautiously and thoughtfully to keep research going safely.

Of course, the pandemic is also occurring alongside renewed and amplified calls for inclusion and equity, particularly as they pertain to anti-Black racism. “Hopefully, we come out of this having grappled with social justice in a way that we would not have as strongly if not for the pandemic, and figure out ways to equitably minimize impacts on the most vulnerable groups,” said Goldhaber-Gordon, professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, who was a founding member of the Equity and Inclusion Committee in the Department of Physics.

The lessons learned during the pandemic may permanently change how science at Stanford is done. Some researchers have pushed their work in directions that have become more pressing during shelter-in-place. Some have learned new ways to run their labs with greater empathy and compassion. Other labs will come out of the pandemic equipped with new virtual capabilities and shared resources that speed up discovery, expand the accessibility of their research and enhance their personal interactions.

Moving online

As a result of her quick reaction to news of the novel coronavirus, Gweon’s online experiments were up and running again within a month. Her lab distilled the hard lessons they learned into guidelines that they then published to help other developmental psychologists make the virtual transition. “It was stressful times but my lab members have been incredible,” said Gweon. “We hosted a webinar and shared all the materials that we developed – like manuals for researchers and for parents – because we wanted other labs to save their time and effort creating them from scratch, and make a quicker, easier transition to online research.”

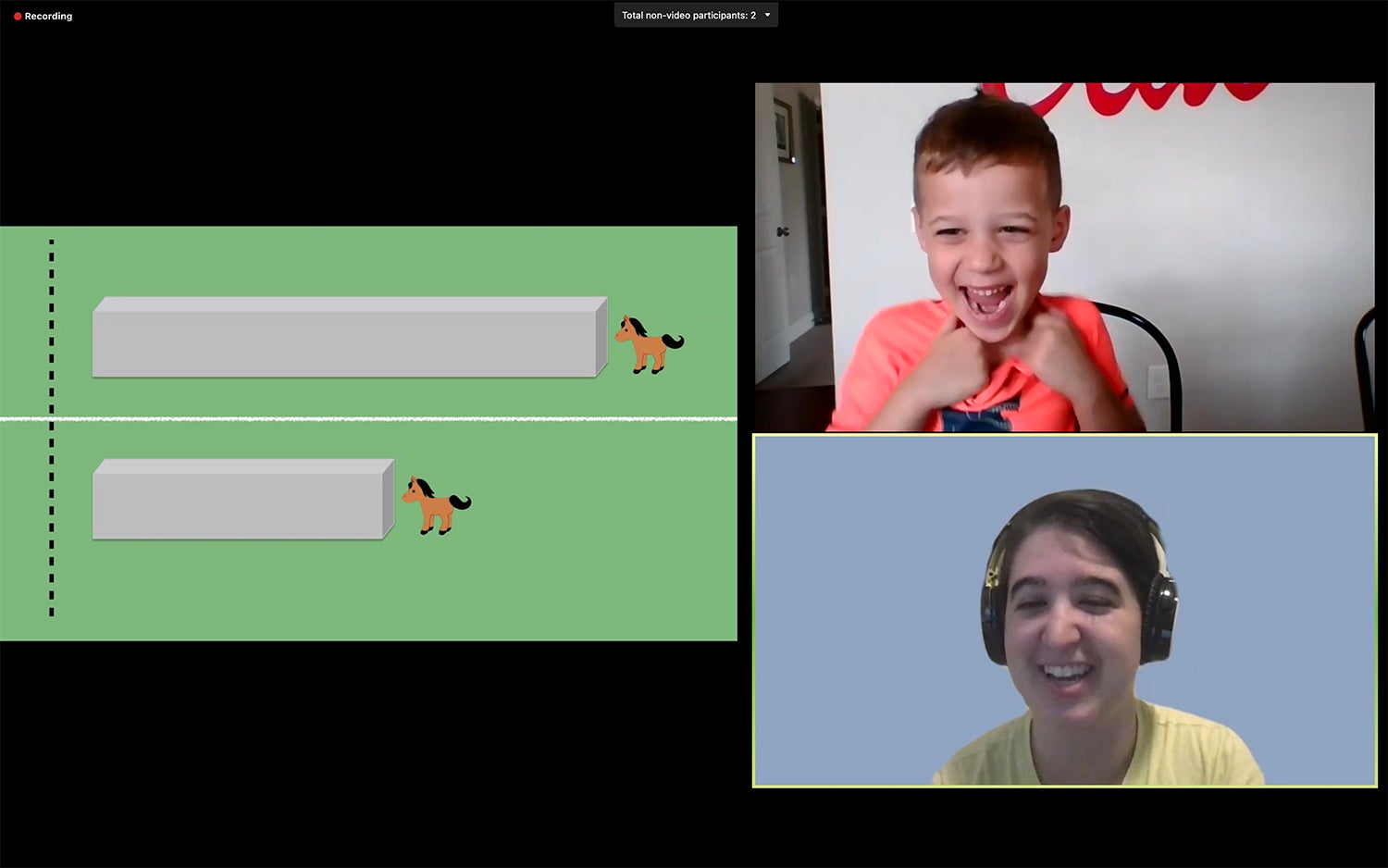

Teresa Garcia, a lab manager for the lab of Hyowon Gweon at Stanford, running a virtual study with a young participant to investigate how children reason about concepts like speed, distance and difficulty. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

Her team also helped launched a website called Children Helping Science to connect researchers with potential virtual study participants, and Gweon has noticed that families seem more eager than ever to get involved.

The Gweon lab is now running 12 online studies. Although they plan to resume in-person studies eventually, Gweon expects online experiments will become permanent fixtures in her research. “Part of the reason why we spent so much time and effort in the beginning was because we didn’t want it to be a temporary thing,” said Gweon. “It also helped us create a vision for where developmental research is going to go, what we can study and how.”

There was less opportunity for members of the Sperling lab to virtualize. In studying how environments change through time and the effect that has had on animals, their work requires a combination of fieldwork and lab analysis. For example, Murray Duncan, a postdoctoral scholar in Sperling’s lab, was forced to cancel his fieldwork up the coast to Canada, which would have featured mobile experimental aquariums used to evaluate how marine organisms respond to temperature changes. To his credit, however, Duncan still proceeded to build a version of these aquariums in his garage, which he is using to study purple urchins and red abalone.

The experimental aquarium that postdoctoral scholar Murray Duncan (of Erik Sperling’s lab) constructed at home in his garage. Through this system, he can measure the oxygen consumption rate of organisms while manipulating water temperature at the same time. Duncan is studying purple urchins and red abalone. (Image credit: Murray Duncan)

Necessity also fostered invention in the Feldman group. For monitoring purposes, a couple Feldman lab members repurposed old cellphones to livestream the temperature of their nitrogen-cooled freezers. The group also doubled the number of meetings they held (virtually) each week to help lab members stay in touch and provide opportunities to check in on one another.

No matter the variety or frequency of communication, however, virtual lab life simply isn’t the same as the real thing, the researchers say. One considerable difference is the loss of serendipitous interactions – pulling a student in for a quick chat as they pass by your office, testing out a hunch because you have a spare moment at the microscope or sparking a collaboration over coffee with a colleague. Everything also has been made all the more challenging by the fact that the pandemic has coincided with a national social justice reckoning about anti-Black racism, several natural disasters and a contentious presidential election and transition.

“We had nothing but time, and we thought that meant we’d still be very productive in other ways,” said Goldhaber-Gordon. “It was a blind spot, though, because it did not acknowledge the severe psychological weight of the situation. Whether there is a concrete hardship someone is facing or whether it’s just existential dread, I think that everyone’s feeling this in their own way and the loss cannot be boiled down to simply how much time we have or don’t have.”

From purely a publishing perspective, this may actually be the most productive time of Sperling’s career so far, but that is due to fortunate timing with respect to projects in his lab. Although he’s had a hard time focusing on work while home – he prefers reading hard copy papers in a coffee shop away from his phone and computer – his team has published numerous scientific papers in recent months because many of his students were already in or near the paper-writing stage of their graduate work when the pandemic began. But his lab’s publishing output, while worth celebrating, doesn’t accurately reflect how hard this year has been, Sperling said.

“When we first went into lockdown, a lot of the time was spent talking about people’s personal situations and trying to listen, at least, even when I oftentimes couldn’t help them more than that,” he added. “It’s not necessarily something that you train for as a scientist.”

In a Campus Conversation last fall about research, Kathryn “Kam” Moler, vice provost and dean of research, encouraged people to advocate for their needs and to help their colleagues and co-workers.

“It’s a really important time to learn how to work together with other people to make sure everybody in the research group is getting what they need,” Moler told the audience. “In the end, there’s no substitute for every individual’s role in helping each other and keeping each other safe. And, honestly, that’s still not enough. People are carrying really, really heavy burdens right now.”

To help ease some of those burdens, Moler’s office established two (virtual) Research Continuity Committees – one for academics and one for operations – in response to the initial shelter-in-place orders. These groups have been helping develop policies for in-person research and inform the university’s priorities for the return to campus and fieldwork.

“It’s really been wonderful, how many people have stepped up to help,” said Moler, who is also a professor of physics and applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “Staff have been working extra hours, and when we asked faculty to serve on these committees, almost everybody said yes, and you don’t usually get that kind of response. It’s also been so valuable that people have been following the right processes and procedures.”

Ramping up

Process and procedure have been at the core of the return to lab work. When Feldman was first able to resume research, only one person could be in the lab at a time. The limit was gradually increased to two per day, and is now up to roughly one person per lab bay. Under current guidelines, labs can have up to one person per 125 square feet of laboratory space (with some special exceptions) and Feldman uses a shift schedule to stay within regulations.

“One of my postdocs had worked at a bar at MIT, so she had a shift work hack for our online calendar,” said Feldman, who is an assistant professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “It’s just one example of how my lab members have done a really great job in dealing with the pandemic.”

Given continued social distancing requirements, Feldman lab members also rigged a movable webcam setup so they can remotely train colleagues on new equipment. Limits on physical proximity likewise informed Goldhaber-Gordon’s decision to keep his cryostat running: Warming it up would have required two people and repeat visits over the span of a week, whereas maintaining the cooling required only one person – with special permission from the university – to feed it nitrogen every few days.

Throughout shelter-in-place the Goldhaber-Gordon lab has continued some experimental work using a second cryostat that had fortuitously already been set up so that measurements could be controlled and results reported over the internet. As lab capacity limits increase, Goldhaber-Gordon has spent significant time researching the best safety procedures for his specific lab, paying attention to details like the face coverings they use and their air circulation system.

“When I first was designing my lab, I learned more about pouring concrete and air conditioning and electrical power than I ever thought I would learn,” he said. “Now I’m doing that again in a new context and I think it would be good if we had a way to share our solutions across campus – while also recognizing that we aren’t experts.”

Only one student is consistently using the Sperling lab for now. Research in the lab may not reach pre-pandemic levels until its members can reschedule their fieldwork in the Yukon and Northwest Territories, which was supposed to be the foundation of the lab’s next set of studies.

“We were going to start a new project in the Yukon and Nunavut Arctic islands. This trip has been in the works for 10 years,” said Sterling. “Daydreaming about new rocks and reading about them in preparation for fieldwork is part of the fun of being a geologist, and I haven’t gotten to do that during the pandemic.”

At present, all university-sponsored travel is suspended until further notice and field research is heavily restricted.

Embracing new tools and resources

Some of the stopgap measures Stanford researchers have implemented to keep their labs functional during the pandemic could, in some cases, become permanent, serving as the basis for hybrid labs of the future that blend virtual and in-person experimentation.

For example, Goldhaber-Gordon plans to convert the second cryostat to optional remote operation and modify the current remote-controlled cryostat to run more measurements simultaneously. He also will alter this cryostat’s cooling system to have a closed cycle, conserving helium (a dwindling natural resource), saving money and student effort each week, and facilitating remote operation.

“We had actually started on these projects before the pandemic,” said Goldhaber-Gordon. “Now, they have all ended up being more challenging than any of us expected; partly because you never guess how complicated things will be and partly because of the present limits on students working in close physical proximity.”

Gweon’s new virtual experiments not only provided a lifeline for her lab – and other developmental psychologists – but, looking to the future, they open up research opportunities and enable more inclusive science.

“By bringing studies online, people can participate from everywhere,” said Gweon. “It helps us recruit a larger, more diverse group of participants – less restricted by location or socioeconomic status. It makes our conclusions much stronger and allows us to address questions that haven’t been able to be answered before.”

Even before the pandemic, the university had set in motion plans to increase access to resources and facilities as part of Stanford’s Long-Range Vision. These strategic platforms provide shared facilities and resources, including expertise and funding, to support interdisciplinary research.

“In light of the pandemic, I think there’s a deeper understanding that, in the modern world, it’s really important to give researchers the tools that they need to be flexible,” Moler said. “We want to make it possible for them to make that pivot without having to spend years writing a proposal for a new piece of equipment.”

Return to abnormal

In trying to be mindful about who continues to be affected by the research closure in disproportionate ways, Moler and other research leaders stress the need to continue prioritizing the scholarship, careers and well-being of trainees (which include students and postdoctoral scholars) and early career researchers – who often have young families, added publishing pressure and, in some cases, less stable funding sources. To address this concern, the committees are currently developing a roadmap focused on bringing additional researchers and scholars back to campus (as allowed by state and county guidance), as well as human subjects for non-essential research.

“There are no easy solutions to the challenges facing us right now, but we’re trying to do what we can by making sure that there are ways for people to share their concerns, and so many people have done so much good work to keep our community safe and to keep research moving forward,” said Moler. “It’s been a really tough year, but I still think the future is bright for research.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.